Living in the generative age

Considering a description

Greetings from the end of a wild May. There’s a lot going on here, which has slowed down these Substacks. I have a lot of AI thinking and scanning to share. So let’s catch up with one big idea.

We’re living in a generative age, and this is a new thing. That’s the concept I came across in this David Wiley blog post.

To summarize the idea: information and communications technology from 1400 to 2022 was essentially about publication. People would create content, then share it to audiences through print, gramaphone, radio, magazines, movie theaters, all kinds of analog systems. The digital world followed suit, although through different formats: Usenet posts, web pages, blogs, podcasts, YouTube, videos, etc. At each point the tech published content, taking it from creators to consumers.

Our information and media habits flow from publication. As consumers, we use online (formerly card) catalogs or stores to find books to read. We can scan a radio dial or skip along Spotify lists to find songs or talk to listen to. We Google for content, and the results are links to publications: websites, pdfs, videos, podcasts, blog posts. As creators, the publication tech radically grounds what we make: an audio track for radio or album, a street video for Instagram Reels, a long chunk of prose for a book.

Generative AI breaks this publication paradigm fairly radically. As users we ask questions, instead of hunting for titles. In response we get new content, as AI bots create stuff on the fly, on spec. Some bots offer links in support of their material, which we can follow, of course, but the priority level is much lower than the content itself.

It’s a subtle but vital difference. For an example, consider this Google search, which has Gemini turned on:

I asked about the impact of Gutenberg’s invention. Google’s search answer (bottom half of the screenshot) is classic, a link to a website the service considered most appropriate. Its AI answer (top half) actually answered my question directly by making words into sentences.

The difference is much more apparent when it comes to images. Searching for “publication” on Google brought up all kinds of photos and drawings. Looking on Flickr for Creative Commons-licensed materials yielded a fascinating and weird array, thousands of photos, like this one:

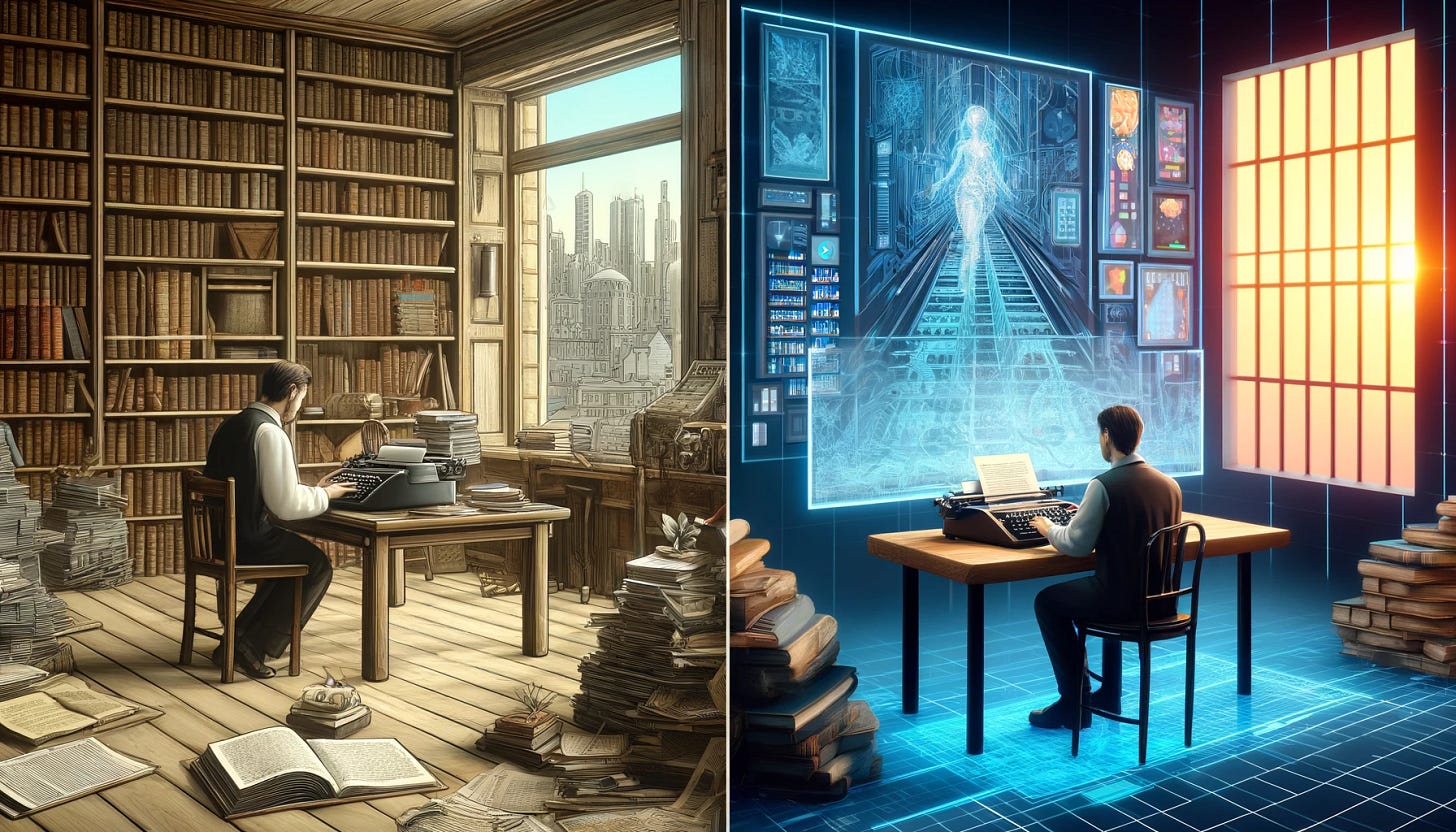

In contrast, I asked DALL-E to draw a contrast between publication and generative AI:

If I wanted to make such an image, I’d have to crack open various tools (paper, Adobe Illustrator, a camera), take and edit a photo, or perhaps actually learn how to draw (I’m horrific at that). Until recently my practice was to get images from Flickr, which are publications. Increasingly I ask AI tools to generate images instead.

Here’s Jonathan Ross, the CEO of Groq describing the idea:

This shift from publication to generation changes user habits. Instead of searching, we ask. Instead of learning how to identify the right keywords and string them together with basic Boolean logic, we study prompt engineering. One involved document or information retrieval, while the other sees stuff generated on the spot.

So we might be standing in the early light of the generative age’s dawn. If that’s true, we need to look ahead for the changes in store as well as the possibilities we have.

…but not so fast. I don’t think the break is that clear. Rather, I think it’s a question of shifting emphasis. That is, we’re moving from a mostly-publication era to a more-generative one.

Starting with search, people do post questions to Google search. That is, sometimes we enter a keyword or a keyword combination, but other times we type in a question. It’s easy to find proof of this in Google’s (AI-backed) autocomplete:

Text-based chatbots predate generative AI by years, even decades. ELIZA dates back to the mid-1960s (I hand-coded one into a mainframe in junior high, circa 1982). Similarly, Amazon and Apple would like us to address oral questions to their Alexa (2013) and Siri (2011) engines, according to their samples and documentation.

The more I look into this, the more I see proto-generative activity before OpenAI released ChatGPT 3. We’ve seen various forms of AI (sometimes just algorithms) in computer games, and now in some tabletop games as well, creating interesting responses to our moves. Procedural games offer something less predictable than “publishing” (different game content appears each run, as opposed to the same game events popping up every play-through). On the back end, websites have been using scripts and databases to generate custom webpages on spec - for an easy example, check out any Amazon product page, especially when you’ve signed into your profile.

Given these caveats, I think we can’t say “the age of publication ended in November 2022; we are now in the age of generation.” We can say, though, that we’re living in a decreasingly publication-centric time and instead are increasingly inhabiting the generative age.

Maybe not. Let me kick the idea around by adding some more objections:

This age might be brief The generative age, such as it is, might not last long. I’ve written about the many existential threats genAI faces: copyright lawsuits, problems with business models, state regulation, quality collapse, cultural resistance. If one or more of these proves decisive and nothing appears to pick up the torch (say, if open source tools don’t get widespread use), then we might be in the middle of The Generative AI Parenthesis or The GenAI Episode.

Maybe it’s not generation, but remixing One good friend with astonishing informatics knowledge argues that “generation” is a misnomer. Instead, tools like Perplexity and Midjourney are more properly understood as very advanced remix engines. They start from preexisting content, chop it into bits, then [insert n-dimensional math and a lot of other functions] a comprehensible output appears.

So in this view, we’re talking something closer to William S. Burroughs and less like a world-transforming bit of supercomputing, at least on the back end. The user or consumer experience might still feel generative, but the underlying reality is remixing. Perhaps the Age of Remix is now upon us.

It’s a new age, but a degenerative one Yes, ok, the generative experience is rising quickly, but it’s a bad one. This objection points to the many hallucinations, errors, and just strangeness emitted by these applications and wants us to recognize them as an essential condition of the new order.

The degenerative age may get even worse, if I may keep ventriloquizing the idea. A growing amount of networked information now stems from generative AI. Its population of errors will likely enter into the next training sets for upgraded and new AIs, reducing their quality in the classic copy-of-a-copy dynamic. The new AIs, weakened by their inputs, will then drive new training datasets, and so on: the Degenerative Age arises.

Thinking of these objections, I can’t fully shake the generative idea. The difference between publication and generation does a decent job of describing my experience with the tools. Yet the term doesn’t quite sit for me. It feels too optimistic, like the opening into some epoch which will be a net positive. “Generative age” also misses some key points, like the remix challenge.

Last year I fooled around with some cultural figures to apply to generative AI and came up with two. The calculator was a powerful shock in the 1970s, once it became an accessible consumer good. I thought we might forgive generative AI its trespasses and treat it like a calculator, that little handy thing which threatened parts of our society. To this I added the mad scientist’s henchman, that energetic yet quasi-reliable figure a bit too eager and, ah, creative to help. I’m still fond of the latter metaphor, but it hasn’t caught on. (Some folks accused me of trivializing the threats AI poses to the world.) And it looks like we’re generally too suspicious or skeptical of AI’s output to truly consider it a reliable tool, like the calculator. AI seems to exist in an interzone of quality, neither sturdy nor wacky.

Perhaps a better term for the unfolding information era is the oracular age. Historically oracles were semi-reliable, capable of giving querents cryptic or clear responses. Some responses would be coded for later revelation, as with the famous pronouncement to Croesus.

Societies venerated their oracles. States and wealthy people supplied them well with support and gifts, hoping to win favorable results, not too dissimilar from our society’s lavishing fortunes on generative AI firms.

Does the oracle seem like a strange figure, too eccentric to describe a digital mainstay? Consider the uncanny experiences you first had with Midjourney or ChatGPT, when the thing responded to you with astonishing creativity or shocking personality. Consider, too, the popularity of apps like Replika and Character.ai, which dive right into the uncanny valley to bring a kind of personality simulacrum to effective enough life for a good number of people. Perhaps that connection between human and silicon is a distant echo of a supplicant hearing the Pythia speak.

Or perhaps Oracular Age goes too far, as its leans into subjective impressions and a bit of literary style. The Generative Age looks more clear and direct in contrast, even if it’s really about remixing, might be brief, and could sour. As generative AI races ahead, eliciting opposition and transformation, that title might be the one we end up with.

Something… was growing old and weak, dying out; and something new, young, energetic, and still unimaginable was in the offing. We felt it like a frost, like a spring in our limbs, the one with muffled pain, the other with a keen joy.

-Harry Kessler (1868 – 1937))

Fantastic process of methodical observations and timescapes here, Brian. The 'remix challenge' is spot on. To a point that I've published in-depth considerations on, the 'Oracular Age' I suggest does indeed go too far, as does the misnomer of Intelligence for that matter. Computational rehash and extrusion of the world is not the same as lived experience, knowledge, intuition and wisdom gained.

Maybe it's just the 'cook' in me but some culinary parallels came to mind that might be useful.

1. Douglas Adams, Hitchhiker's Guide - where the ship had a food generator (presumably from some elemental ingredients and a built in body of knowledge about food) that when asked for a cup of tea made "“something almost, but not quite entirely unlike tea”

2. the TV show 'Chopped' where chefs attempt to make a well constructed and cohesive meal from a random (even evil) selection of ingredients. In this case the skill and expertise of the chef is the critical difference between amazing results and a hot mess.

3. From Neal Stephenson, the "Matter compilers receive their raw materials from the Feed, a system analogous to the electrical grid of modern society. The Feed carries streams of both energy and basic molecules, which are rapidly assembled into usable goods by matter compilers." (wikipedia) -- including food. No indication of quality of the experience.

Can AI production be similarly broken down into - what are the ingredients/elements of construction, what is the 'expertise' of construction. In #3, a key part of that discussion is who provides the raw materials... you can't have "generation" or remixing without the publication as ingredients.... no?