Greetings from July in northern Virginia, where the sun and humidity compete to see which can clobber us most thoroughly.

I’ve just returned from an anniversary date at Niagara Falls, on the Canadian (better) side. My wife and I celebrated thirty-two years with some astonishment.

That photo is from a neighboring tower, and might suggest a theme for today’s post: chaos, falls, falling, turbulence, cataracts. Because we’re talking about AI and economics this time. I’m going to share recent developments in actual uses of AI, AI business models evolve, investment boom or bubble, and AI and the world of work, followed by some reflections. Links to supporting documents appear at each point.

(If you’re new to this newsletter, welcome! This is one of my scan reports, which are examples of what futurists call horizon scanning, research into the present which looks for signals of potential futures. We can use those signals to develop trend analysis, which we can use to create glimpses of possible futures. On this Substack I scan various domains where I see AI having an impact. I focus on technology, of course, but also scan government and politics, economics, and education, this newsletter’s ultimate focus.

It’s not all scanning here at AI and Academia! I also write other kinds of issues; check the archive for examples.)

Now, on with the scan. You might want some coffee or tea with this one.

Actual uses of AI

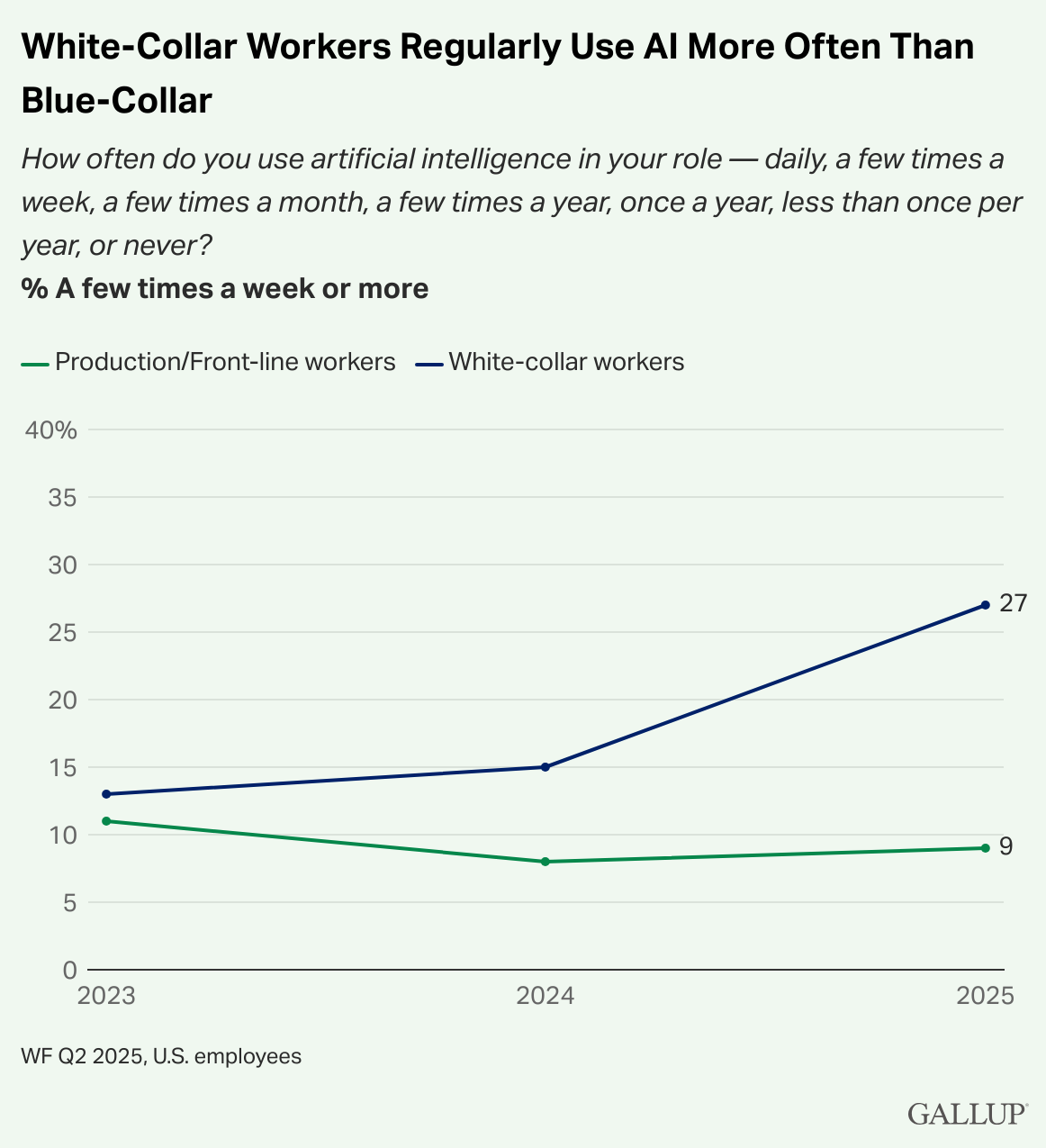

It’s hard to get a good sense of when and how people actually use the technology, but surveys give us a start. A recent Gallup poll looked at people using AI at work found that growth has been steady, roughly doubling over the past two years:

Yet note that the numbers remain low in terms of frequency, with daily AI work not cracking 10%.

Gallup also sliced its data by type of work and you can see white collar use racing far past blue-collar:

I found related data from Apollo Academy, which asked companies (not workers; I suppose respondents were PR staff or CTOs) about their use of AI. Again, we haven’t cracked the 10% level:

The curve is generally upwards, as you can see.

Here I must offer my repeated caution on AI surveys, given that people have all kinds of reasons to answer, ah, creatively when self-reporting.

We can also find examples of businesses formally adopting AI. Goldman Sachs just turned an AI assistant pilot project into a company-wide service. According to Yahoo Finance, “The GS AI assistant will help Goldman employees in ‘summarizing complex documents and drafting initial content to performing data analysis,’ according to the internal memo.” Starbucks is rolling out its own assistant, Green Dot Assist, to help staff find information:

Instead of flipping through manuals or accessing Starbucks’ intranet, baristas will be able to use a tablet behind the counter equipped with Green Dot Assist to get answers to a range of questions, from how to make an iced shaken espresso to troubleshooting equipment errors. Baristas can either type or verbally ask their queries in conversational language.

AI business models evolve

The quest for making generative AI profitable continues. Perplexity released an even more advanced tier, Perplexity Max, which gives users access to new features faster along with more access to their Labs feature. The price is high: $200 US per month.

Partnerships continue to appear. In June Bloomberg broke a story about AI audio generating companies Udio and Suno negotiating with traditional music companies about licensing fees.

Investment boom or bubble?

Huge torrents of money keep flowing into AI. Anthropic now takes in $3 billion per year, apparently. NVidia just cracked the $4 trillion valuation barrier.

Infrastructure is key to AI investment. The Stargate project seems to be growing, as OpenAI agreed to buy more data from Oracle - a lot of data, “about 4.5 gigawatts of data center power.” In dollar terms, “Oracle announced that it had signed a single cloud deal worth $30 billion in annual revenue beginning in fiscal 2028 without naming the customer. This Stargate agreement makes up at least part of that disclosed contract…”. Amazon is building an immense datacenter in Indiana, called Project Ranier, for Anthropic’s AI effort. The New York Times notes that “Amazon… has invested $8 billion in Anthropic.” A group of Chinese AI companies are building an immense complex in Xinjiang:

A Bloomberg News analysis of investment approvals, tender documents and company filings shows that Chinese firms aim to install more than 115,000 Nvidia Corp. AI chips in some three dozen data centers across the country’s western deserts. Operators in Xinjiang intend to house the lion’s share of those processors in a single compound — which, if they can pull it off, could be used to train foundational large-language models like those of Chinese AI startup DeepSeek.

Money is also going to the hiring competition. Meta has taken the lead by pouring out funds to lure AI experts to its new effort to achieve artificial general intelligence (AGI) then superintelligence. Along these lines the company snapped up three OpenAI researchers. Meta purchased nearly half of ScaleAI, while hiring the smaller firm’s CEO, all for nearly $15 billion. Meanwhile Meta is trying to raise nearly $30 billion in financing to build out more AI infrastructure.

Elsewhere in acquisitions, Grammarly announced it was buying Superhuman, an AI email service. Neither party announced terms, but Reuters noted that the target company “was last valued at $825 million in 2021, and currently has an annual revenue of about $35 million.”

At the same time more friction is appearing. Tensions are showing in the Microsoft-OpenAI relationship, according to some reporting. OpenAI wants more independence so it can become fully for-profit. MS’s AI CEO, Mustafa Suleyman, soft-pedaled this in a recent podcast. Elsewhere X (formerly Twitter) changed its terms of service to block anyone else from using its content to train AI. After all X has its own AI, Grok.

At the same time the emerging industry faces potentially serious problems. There’s a geopolitical angle, as the US-China trade war/decoupling has cut rare earth supplies to American companies, which can threaten data center growth. There’s also a partnership angle, as news sources are seeing fewer click throughs as AI-generated summaries grow, according to one report. (Yes, I’m still working on my AI vs the Web post)

AI and the world of work

How might AI impact labor? This question has been one I’ve focused on and it remains open, fraught, and fiercely contested.

One way forward is the classic industrial revolutions’ pattern of replacing labor (workers) with capital (AI). Several CEOs of major companies have made some high profile statements along these lines. The Wall Street Journal has a good round-up:

“Artificial intelligence is going to replace literally half of all white-collar workers in the U.S.,” Ford Motor Chief Executive Jim Farley said in an interview last week with author Walter Isaacson at the Aspen Ideas Festival. “AI will leave a lot of white-collar people behind.”

and

Amazon CEO Andy Jassy wrote in a note to employees in June that he expected the company’s overall corporate workforce to be smaller in the coming years because of the “once-in-a-lifetime” AI technology. “We will need fewer people doing some of the jobs that are being done today, and more people doing other types of jobs,” Jassy said.

The article notes that this is something of a shift, with CEOs being open about this desire to automate labor. Just a few months ago this had been an offline sentiment: “In private… CEOs have spent months whispering about how their businesses could likely be run with a fraction of the current staff.”

A British government study gives some evidence for this view, finding that government workers used AI to free up two weeks per year of work. Meta is putting this into practice, offering automated marketing services. New York State has recognized this, apparently asking companies to tell that government when they lay off people because of automation.

A recent New York Times article helpfully points out one divide in the automation-jobs area. Will we see AI replace younger workers early in their careers, cutting down entry-level hires? Or will younger workers use AI to advance and threaten their elders? This is a major question:

If entry-level jobs are most at risk, it could require a rethinking of how we educate college students, or even the value of college itself. And if older workers are most at risk, it could lead to economic and even political instability as large-scale layoffs become a persistent feature of the labor market.

And yet. There don’t seem to be many layoffs due to AI, according to one interesting report from the delightfully named career placement outfit Challenger, Gray & Christmas. Out of hundreds of thousands of layoffs they found only… 75 directly attributed to AI replacement. Technology issues more broadly construed did cause more cuts: “Technological Updates, including changes related to automation and AI implementation, have led to 20,000 job cuts in 2025.” Far larger causes were DOGE and tariff-driven restructuring, not to mention technology companies cutting jobs to focus on AI.

An NBC analysis offered some more spins. Some companies might be freezing hiring or cutting jobs for non-AI reasons, but want to invest in AI software against the possibility of AI automation down the road:

Many firms are currently under tremendous pressure to cut costs given the generally uncertain economic environment spurred by the heavy cost of Trump’s tariff policy and worries about rising inflation. As a result, some companies are diverting spending that would otherwise be going to hiring more employees and shifting it toward AI software.

“There’s basically a blank check to go out and buy these AI tools,” said Josh Bersin, CEO of The Josh Bersin Company workforce consultancy. “Then they go out and say, as far as head count: No more hiring. Just, ‘stop.’ So that immediately freezes the job market.”

More cynically, some companies might blame employment actions on AI to cover their non-AI strategies and operations:

In a note to clients, analysts with the consultancy Capital Economics said not all mentions of AI by businesses discussing their financial picture should be taken at face value.

“For some firms, AI is a way to spin job losses driven by poor financial performance in a more positive light,” they wrote.

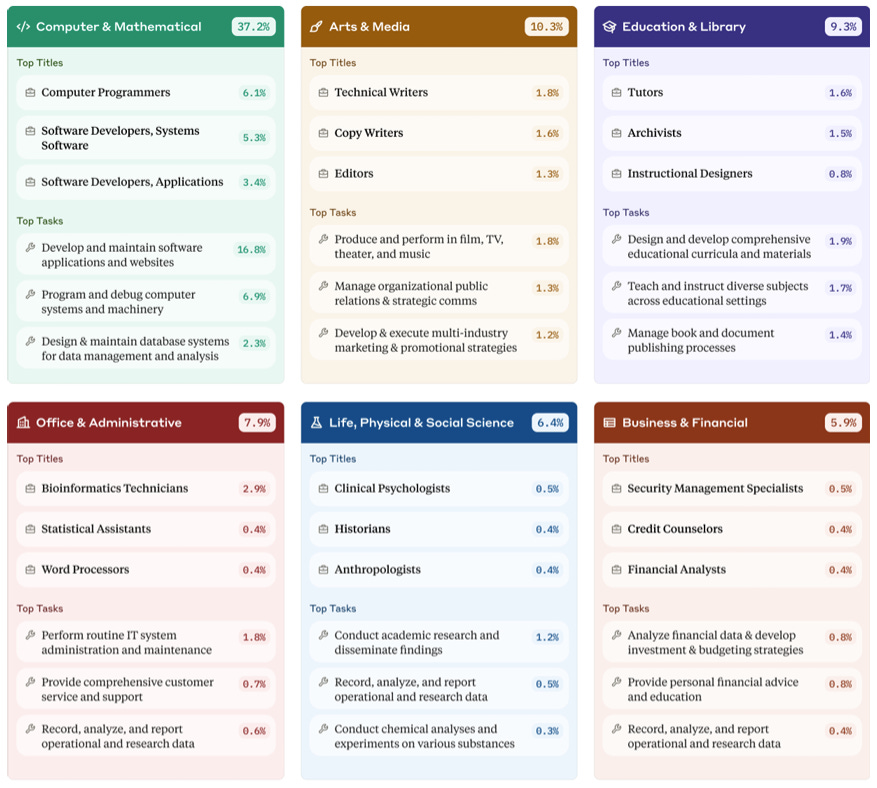

Last point on this topic: Anthropic researchers posted a fascinating paper looking at a huge dataset of people using Claude, then mapping those uses against US Department of Labor categories. It’s an interesting approach, focusing on tasks performed rather than jobs held, and the results make some sense.

First, more than one third of conversations fell under the header of computing and math skills: “computer-related tasks see the largest amount of AI usage.” Arts and media trailed that category, followed by education, administration, non-computer sciences, and lastly finance.

Second, the research team applied another skills framework, less identified to specific professions, to their dataset of Claude’s responses and came up with this list:

Note the humanities-associated skills in the lead, which gives support to the argument that the humanities prepare people well for AI conversations. You can also see the physically-involved skills clustering to the bottom.

Third, the researchers extrapolated that the jobs most in danger of AI automation were middle-ish range in terms of income and training (“we find peak usage in mid-to-high wage occupations”). The more jobs involved physical activity, like health care provision or vehicle maintenance, the less exposure they had to AI.

Fourth, the paper broke down conversations into two categories: those which had the AI automate a human task, vs those where the software augmented a human doing a task. Some examples:

The researchers found conversations roughly evenly split on this axis: “automative behaviors (43%) where users delegate tasks to AI, and augmentative behaviors (57%).”

Reflections

What can we learn from these developments, especially looking ahead? I’ll keep this quick, as Substack informs me I already shattered the “too long for email” barrier.

The investment boom continues to thunder along, with money pouring down around the world, especially in physical infrastructure. There are few signs of the much-predicted bubble popping, but I’m watching and probing for them. Underappreciated is the geopolitics of AI, especially the US-China struggle. AI is built into that new cold war, and the complex and dynamic conflict keeps hitting AI.

AI adoption seems to be growing among consumers, but remains a relatively small part of the labor and business economy so far. Which users and professions make most use of the technology seems to be all over the place so far, besides the clear inroads made in computer science and IT.

Similarly the job loss/replacement situation looks murky, as it did in our last economics scan. If we follow the old industrial revolutions’ pattern we should see new job types appear, like my “AI wrangler,” but that doesn’t seem to be happening at scale.

Handa, Tamkin et al’s distinction between automation and augmentation is one we should bear in mind as we consider AI not just in economics but in many other domains.

That’s all for now. Next up is a post on challenges of teaching with AI.

(thanks to Glen McGee and Peter Shea)

Really thoughtful analysis, thank you. It's lovely to see that you and your wife enjoyed Niagara Falls.. just 20 minutes from me!